Cosmic Dance: the musical life of Naresh Sohal

29th August 2023

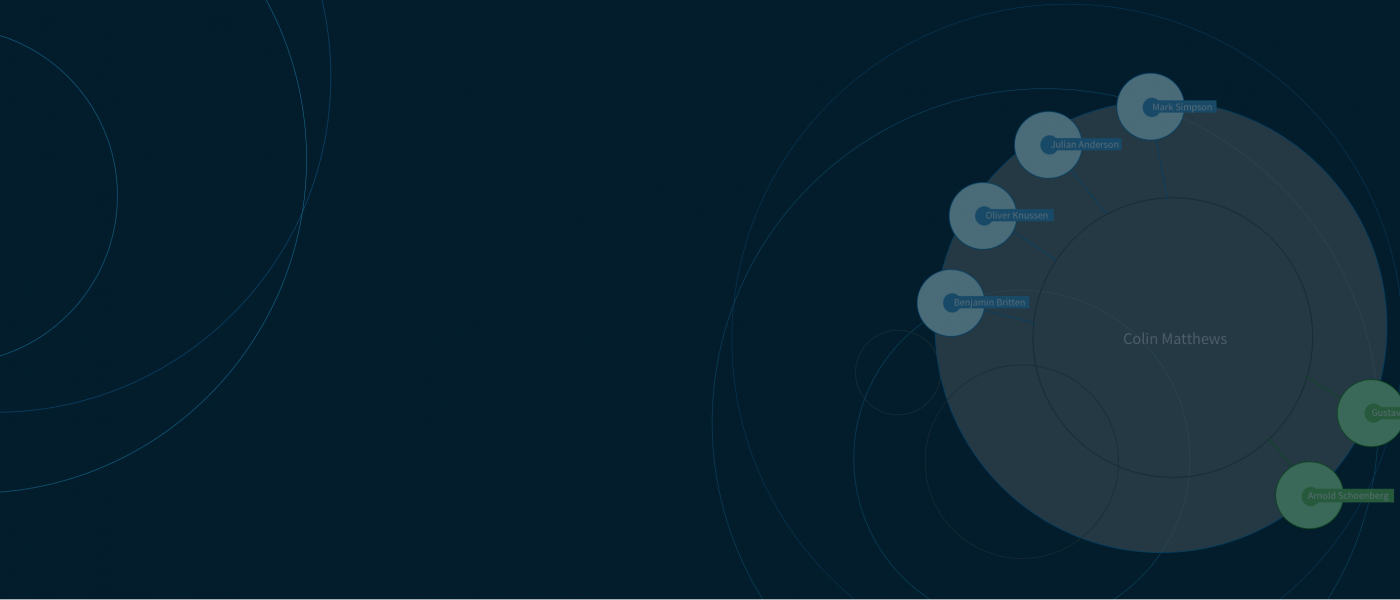

Articles NMC RecordingsBorn in pre-Independence India, the composer Naresh Sohal (1939 – 2018) forged a unique compositional voice, and built up an extensive body of work that imaginatively expresses the philosophy of the Indian subcontinent through the colourful use of western classical music traditions. Suddhaseel Sen (musicologist) and Janet Swinney (writer and Naresh's widow) collaborate to tell the story of the composer's life and works.

Naresh Sohal (1939–2018) was one of the most remarkable composers of his generation, a man of ambition, talent, determination and philosophical insight. By the time of his sudden death in 2018, he had produced an extensive body of work that included major pieces for orchestra, chorus and soloists; intimate and innovative chamber works; a ballet score; two music theatre pieces; the scores for several television programmes; songs in the North Indian ghazal tradition and film songs for the Bollywood director Dev Anand (Goldie).

He received eight commissions from the BBC, two of which were for major Proms pieces, and had more than forty broadcasts of his work. He was the first composer to receive a bursary from the Arts Council of Great Britain, he served on the BBC music committee for a number of years and, in 1987, he was awarded a Padma Shree (Order of the Lotus) by the Government of India for his services to music.

Naresh was born in Harsipind, Punjab, in pre-Independence India. There was no tradition of music in his family, although his father, Des Raj, was an Urdu poet who hosted poetry melas (gatherings) at his home, with his young son in attendance.

A young Naresh Sohal composing in the 1960s

Naresh had no training in either western or eastern music, but he showed a talent for music early on, learning popular songs from the radio and playing them on the harmonica. By the time he was a young man, studying Maths and Science at college, he and a friend who played the guitar were performing rock and roll numbers at college dances to entertain their fellow students. He was a contemporary of Jagjit Singh, who went on to become India’s most famous singer of ghazals, and attended the same college as him in Jalandhar, Punjab.

It was during his student years that Naresh developed an interest in composition, writing waltzes and marches for the Punjab Armed Police band. Eventually, he threw over his final exams and set out for Bombay in the hope of gaining a job as a musician in the film industry there.

While he was sitting out the monsoons in Bombay, waiting for an employment opportunity to present itself, he heard his first piece of western classical music, a broadcast of Beethoven’s Eroica symphony on All India Radio. This was a transformative experience, awakening in him a sudden realisation of the full power of the orchestra and its ability to manifest complex sound worlds. He immediately begged his father to allow him to travel to Europe so that he could become a composer of western classical music.

The aspiring composer arrived in the UK in 1962 with only the permitted £2 in his pocket. His early experiences of life and work in London in an age of explicit discrimination were grim. He took evening classes in composition at a couple of Adult Education institutes but found them uninspiring. Eventually, he managed to secure employment as a copyist with Boosey & Hawkes, the music publisher. This was a game changer and provided an immersive experience from which he was able to assimilate much about compositional techniques in contemporary music. With his steady hand and his meticulous approach, it wasn’t long before he was the company’s top copyist and was able to work on a freelance basis.

Naresh Sohal at work (photo credit Janet Swinney)

Now, Naresh moved on to two further orchestral works, Aalakhyam I and Aalakhyam II. Even at this early stage of his career, some of his personal characteristics are evident, such as the turn towards the macrocosmic aspects of nature for inspiration; the tendency to think in terms of large-scale, single-movement musical structures; the use of a wordless soprano voice over and above the timbral palette of the orchestra, and a reluctance to belong to any particular ‘school’ or easily identifiable coterie.

He was also busy at this point writing a number of chamber works for voice and various instruments, and Jane Manning, who was almost his exact contemporary, was often the soloist in these pieces, as in Night’s Poet, a setting of a poem from Rabindranath Tagore’s Fruit Gathering.

He copied works by a diversity of composers including William Walton (Richard III), John Ireland, Gustav Holst, Andrzej Panufnik, Richard Strauss, Léo Delibes, Bedřich Smetana (The Bartered Bride), Sergei Prokofiev (Third Symphony), Aaron Copland (Prairie Journal), Johann Sebastian Bach (The Art of Fugue), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Frederick Delius, Peter Maxwell Davies, Béla Bartók (Concerto for Two Pianos, Percussion and Orchestra), Igor Stravinsky (Oedipus Rex) and Benjamin Britten (Billy Budd and The Turn of the Screw). He was particularly interested in the approach Iannis Xenakis adopted to produce his piece, Eonta, and this opened up a whole new line of thought for him.

By now, he was trying his own hand at composition, and under the mentorship of the composer, Jeremy Dale Roberts, began to flourish. In 1965, he completed his first two major scores, Asht Prahar for orchestra, followed by the choral work, Surya, for chorus, percussion, and flute. Asht Prahar is based on the Indian division of the day into eight temporal units, four each for day and night. The composer’s talent soon attracted the attention of the Society for the Promotion of New Music (SPNM), who sponsored the first performance of Asht Prahar in 1970. The performance was given by the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Norman del Mar at the Royal Festival Hall, London.

By 1970, Naresh was composing full-time, supported by an annual bursary from The Arts Council. In 1972, he was invited to the University of Leeds by Prof. Alexander Goehr, to produce a dissertation on quartertones. The assignment was started, but composition was too much of a draw, and the composer returned to London with it incomplete.

The first half of this decade, saw important performances of new works almost every year. These included premieres of Aalaykhyam II (1972) in February 1973 by the English Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Andrew Davis; Kavita III (1972), composed for Jane Manning and Barry Guy (double bass) – this piece was taken on an Arts Council tour – and the chamber piece Hexad, first conducted by Elgar Howarth.

Dhyan I (1974), a work for cello and small orchestra, was premiered by the tragically short-lived virtuoso cellist Thomas Igloi (1947-1976) with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under David Atherton, in 1975. The same year, Kavita II was one of the BBC’s entries for the International Rostrum of Composers held in Paris. It was chosen as one of the best ten entries and subsequently broadcast on several radio stations throughout Europe.

The works from this period are stylistically diverse: the austere soundscape of Dhyan I, in which the composer made creative use of his study of quarter tones, sounds very different from the exuberant Asht Prahar, while the chamber work Octal (1972) features electronic devices. Fortunately, the recording of Dhyan I with Thomas Igloi still survives.

The late 1970s saw premieres of largely chamber and vocal pieces (with accompaniment by chamber forces). But in the 1980s, Naresh returned to orchestral composition, now with added vocal (and sometimes choral) forces.

The first of these was the result of a commission he received for the 1982 BBC Proms, and was a setting of the Anglo-Saxon poem, The Wanderer, for baritone, symphony orchestra, and chorus. In this piece, he adroitly harnesses his fertile orchestral imagination to provide a dramatic reading of a poem that one would normally read as ‘personal’. Yet, his division of the work into sections for solo baritone and chorus sounds natural, and the opening motif on tremolo violins returns from time to time with striking effect in the course of the 50-plus minute work. The theme thus provides a structural arc connecting the various stanzas that are distinguished from each other by means of a masterly handling of varied choral-orchestral textures allied to an excellent sense of proportion.

Naresh was drawn to the poem on account of its ‘existential bleakness’, and this led him to omit its consolatory Christian ending. The premiere of The Wanderer was given by David Wilson-Johnson, baritone, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the BBC Chorus, and the BBC Singers, under the baton of Sir Andrew Davis.

The second important work from this period was composed after Naresh moved to Edinburgh in 1983. This was an elegiac setting, in English translation, of Tagore’s From Gitanjali, a work for baritone and orchestra. The work was premiered in New York, in the composer’s presence, by John Cheek and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Zubin Mehta. Like Sir Andrew Davis, Mehta championed Naresh’s works, commissioning two other large-scale pieces from him.

That same year, Tandava Nritya (Dance of Death and Re-Creation) was completed. This was commissioned by the British Council for the London Symphony Orchestra for a planned tour of India. Unfortunately, the tour did not materialise, but when the work was eventually premiered in 1993, by the BBC Scottish Orchestra under David Davies at the Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow, its raw, pulsating energy almost lifted the roof off the building. Unfortunately, the composer did not get to hear this as he had received word that his mother was dying and was on his way to India.

Tandava Nritya was followed by a Violin Concerto for the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, premiered in 1986 with the accomplished Chinese violinist Xue Wei as the soloist, and Martyn Brabbins conducting.

In 1987, the Government of India awarded the prestigious Padma Shri (Order of the Lotus) to the composer for his services to western music.

The mid-1980s to the mid-1990s was a period during which Naresh devoted himself to works for the stage and for television. These include the ballet Gautama Buddha (1987), choreographer Christopher Bruce, which was premiered in Houston, Texas, by Houston Ballet, who then brought it to the Edinburgh Festival in 1989.

Premiere of Naresh's ballet, 'Gautama Buddha' in Houston, Texas, 1989. Principal dancer, Li Cunxin (photo credit Houston Ballet)

That same year, the Paragon Ensemble gave the first performance, in Glasgow, of Madness Lit by Lightning, a music theatre piece about human degradation, for which Trevor Preston, better known for his extensive work in television drama, wrote the libretto. Other projects from this period included the scores for the award-winning programme Sir William in Search of Xanadu, directed by Barrie Gavin, and produced by Scottish Television; and Monarchy –The Enchanted Glass, also for Scottish Television. The composer’s Scottish period ended when he returned to London in 1993 because of the rise in nationalism and a steep decline in Arts Council funding.

In 1996, the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Martyn Brabbins gave the first performance of Lila, a major orchestral work begun in 1991. This is a musical account of the process of enlightenment as described in Hindu philosophy and experienced through meditation. The seven interconnected sections of the work – Earth, Water, Fire, Air, Ether, Consciousness, and Union – led the composer to rarefy orchestral textures as the piece progresses. The ethereal closing section, in which a wordless soprano voice is combined with the sonorities of the clarinet, flute, and upper strings, is among the most beautiful passages in all of Naresh’s musical output. Along with The Wanderer and Tandava Nritya, Lila is among the most accessible of his large-scale works, and all three deserve to be better known.

Naresh continued to write until his death in 2018. During the last two decades of his life he produced a range of small and large-scale works. Many of these display a more obvious determination to showcase Indian culture and thought than his earlier works. The orchestral piece Satyagraha, commissioned to mark the fiftieth year of Indian independence, and first performed in 1997 at the Barbican by London Symphony Orchestra under Zubin Mehta, was followed by a Viola Concerto for Rivka Golani (2002), in which he used Indian drums and tabla among the orchestral instruments. The tabla also featured in Three Songs from Gitanjali, settings of three Tagore poems for soprano and string quartet, commissioned by the Spitalfields Festival, and first performed in 2004.

By now, Naresh had begun to set texts in Indian languages. The Three Songs from Gitanjali are settings of Tagore’s texts in the Bengali original, while Songs of the Five Rivers are settings in Punjabi, the composer’s mother tongue, of poems by the classical Punjabi poets Bulleh (or Bullay) Shah and Waris Shah. The latter piece is unique among Naresh’s output in its strong hints of Indian folk music. The talented and much-lamented soprano, Sally Silver (1967-2018), set herself the challenge of learning these pieces in these languages that were unfamiliar to her and delivered the first performances with great assurance.

In 1999, Naresh completed the choral-orchestral Hymn of Creation. This is based on mantras on the theme of creation from the Rig Veda and is set both in English and Sanskrit. The work is the subject of some contention with the BBC, the composer believing that he had a commission from them to write it, and the organisation denying all knowledge of this once it was completed. Sadly, in this age of inclusion and diversity, it still awaits a first performance.

The composer’s next large-scale work, The Divine Song, for narrator and orchestra, has a more fortunate history although its arrival went, basically, unnoticed in the UK. The work is based on the first two chapters from the Bhagavad Gita, which itself is a part of the Indian epic The Mahabharata. The piece was commissioned by Zubin Mehta for his seventieth birthday in 2006 and was first performed in Tel Aviv by the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra in 2010, with the narration in Hebrew. There were subsequent performances in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. The idea of having a narrator rather than a singer was suggested by Mehta himself and this means that, with a little effort on the part of a translator, that the work can be performed in any language. In further performances in January 2011, given by the Staatskapelle, Berlin, with Stefan Kurt as the narrator, again with Zubin Mehta conductor, the language of narration was German. The composer employs three basic musical themes: one associated with war, and the other two with Krishna (using the pitch classes of raga Bhairavi) and Arjuna (using the pitch classes of raga Bhairav).

Naresh’s last large-scale composition was The Cosmic Dance, commissioned by the BBC for the 2013 Proms season. It was premiered by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, under Peter Oundjian. In this piece, the composer returns to the cosmic theme that underpins a number of his major works, being inspired both by modern science and by Hindu philosophy. The work opens with a musical evocation of time before the Big Bang took place, a reference to the Rig Veda, in which it is stated that in the beginning, there was non-being, which remains forever. This notion forms the idée fixe of the piece.

Naresh at the 2013 BBC Proms performance of 'The Cosmic Dance' with conductor Peter Ounjian (photo credit Chris Christodoulou)

The Cosmic Dance is stylistically eclectic and incorporates elements that are normally not to be found in Naresh’s work. It opens with a haunting theme for a solo saxophone over hushed strings, and gradually unfolds to incorporate harmonically dissonant and rhythmically agitated passages, often scored for brass or strings, both elements that are characteristic components of his large-scale orchestral works. What is less usual is the presence of some more overtly tonal elements, such as a waltz melody, a lyrical duet for violin and cello and a solo violin passage that comes near the end of the piece.

In some ways, then, the trajectory of Naresh’s development from being a composer of microtonal, abstract music with unusual timbres, through a period of neo-Romanticism, to a deeper engagement with non-Western languages and musical idioms, reflects some of the major shifts that have taken place in the latter half of the twentieth century in the world of Western music. Yet, there are underlying features that unify his music and make it distinctively his own. It must also be remembered that, unlike Chinese, Japanese, or Korean composers, Naresh had little institutional support from India, where Western music has never had any significant popular base, especially in the post-Independence era. In the light of the very considerable limitations within which he had to work, his ability to create a body of large-scale works is, in itself, a remarkable achievement.

Naresh Sohal (photo credit Janet Swinney)

Naresh’s voice is a unique one in western contemporary music. He created a sound world that was colourful, daring and innovative. He loved working with large forces but could also produce compelling and imaginative chamber pieces. He made use of some of the nuances of Indian classical music but insisted that he was not interested in the gimmickry of melding two musical traditions together. Instead, the philosophy of the Indian sub-continent was what concerned him. His aim was to give expression to ideas first formulated in the Upanishads and the Vedas, and to use the forces afforded by Western classical instruments and artists to best advantage to do it. He dedicated much of his musical life to this goal. His dedication and achievements set an important an important precedent for young people of BME origin everywhere.

In 2023, Toccata Classics released a CD of Naresh’s piano music with Konstantinos Destounis as the soloist.

‘Much of Sohal’s piano music is terrifyingly virtuosic. Konstantinos Destounis is brilliantly on top of every note. The piano is actually a percussion instrument. The intensity of percussiveness stands out proudly in Sohal’s piano music.’ – Alan Cooper, British Music Society (BMS), August 2023.

The release of a CD of four of the composer’s five string quartets with the acclaimed Piatti Quartet is planned for next year, supported by the Ralph Vaughan Williams Foundation.

Works from the earlier part of Naresh’s career are published by Wise Music Classical.

Works from the later part are published by Composers Edition.

Suddhaseel Sen, musicologist - Suddhaseel Sen holds PhDs in English from the University of Toronto and Musicology from Stanford University. He is Associate Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Bombay.

Janet Swinney, writer – author of 'The House with Two Letter-Boxes' (Fly on the Wall Press, 2021) and 'The Map of Bihar' (Circaidy Gregory Press, 2019). Janet is the widow of the composer and manages his musical estate: sohalestate@gmail.com

A longer version of this article accompanied by the transcript of an interview with the composer appears in the latest edition of 'Groniek', the academic journal of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands.

NMC's Discover platform is created in partnership with ISM Trust.