Spherical Sound: from Ambisonics to Atmos

30th May 2023

Articles Huddersfield Contemporary RecordsNicholas Moroz, Artistic Director and co-founder of Explore Ensemble, delves into the intricate recording process and technology behind Perfect Offering, the ensemble's new album. As the first NMC release to be available in a 3D audio format, listeners on Apple Music and TIDAL can use the platforms' integration with Dolby Atmos to realise each track of the release as an immersive, spatial mix. Read all about it below.

On our new album Perfect Offering, Rebecca Saunders’ phantasmagoric piece murmurs, a ‘spatial collage’ for 9 soloists who surround the audience, posed a unique recording challenge: how do you represent a surround piece in stereo, and more importantly, how do you make it sound good?

Fortunately, we have many tools today to help solve this problem, and excitingly, as ‘consumers’ today we now have access to a new means of experiencing spatial sound without huge speaker systems, just with your headphones: Dolby Atmos.

This album is my first Atmos production, as well as HCR’s and NMC’s. In this post I’d like to explain what Atmos is, and give an overview of my specific approach, especially as in the end I took a rather idiosyncratic path, involving a whole new layer: ambisonics. So, here is a sort of dummy’s guide to both (with a few technical nuggets thrown in for those more au fait), a recollection of my process, and and explainer of why all of this is so exciting.

You can also listen to clips of all four pieces on the album while reading (or stream it in full here).

Dolby Atmos

Dolby Atmos developed out of the film world, where engineers had to create several different mixes for the same film tailored to different speaker configurations such as 5.1, 7.1, 9.1, 5.1.4 and so on (those numbers refer to first the speakers around you at ear level, second the subwoofer, and third, if any there at all, overhead speakers). To simplify the process and reduce workloads, Atmos allows engineers to create a single virtual mix in the studio without (in theory!) having to worry about how it will be decoded for specific setups; the Atmos hardware and software embedded in your sound system takes care of that final stage (decoding). This means that engineers can produce a single mix which, with care, can be decoded across different formats, from stereo and binaural (2 channels) to countless surround formats.

More recently, with the adoption of Atmos by streaming platforms like Apple Music and Tidal, Atmos has become available to consumers by means of a headphone mix. Furthermore, Apple’s Spatial Audio in combination with their fancier AirPods allows head tracking, so, just as with a VR headset, you can move your head around the fully immersive sound scene, and it creates the illusion of the sound coming from all around you, rather than the sound coming from inside your head (the usual headphone experience). It’s very cool, and although perhaps most pop tracks will always prefer stereo, murmurs is a perfect use case for Atmos to give the listener a totally new experience of the music.

But, how do you do it, how do you create this virtual mix?

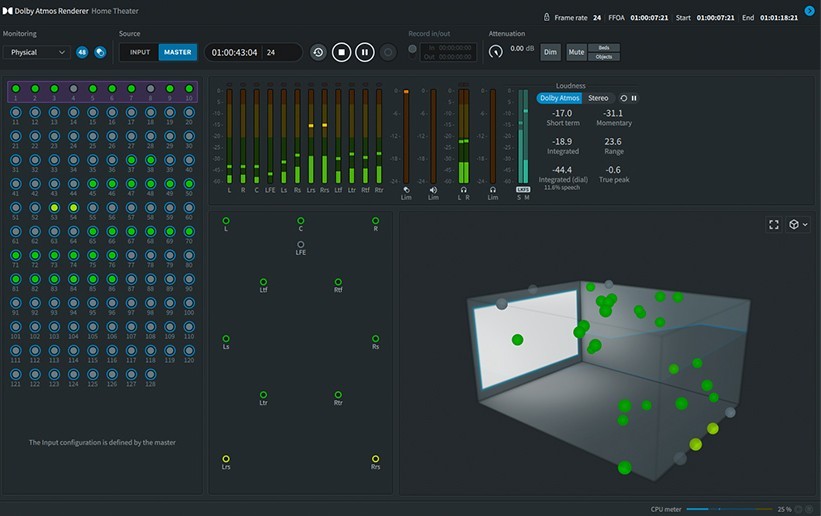

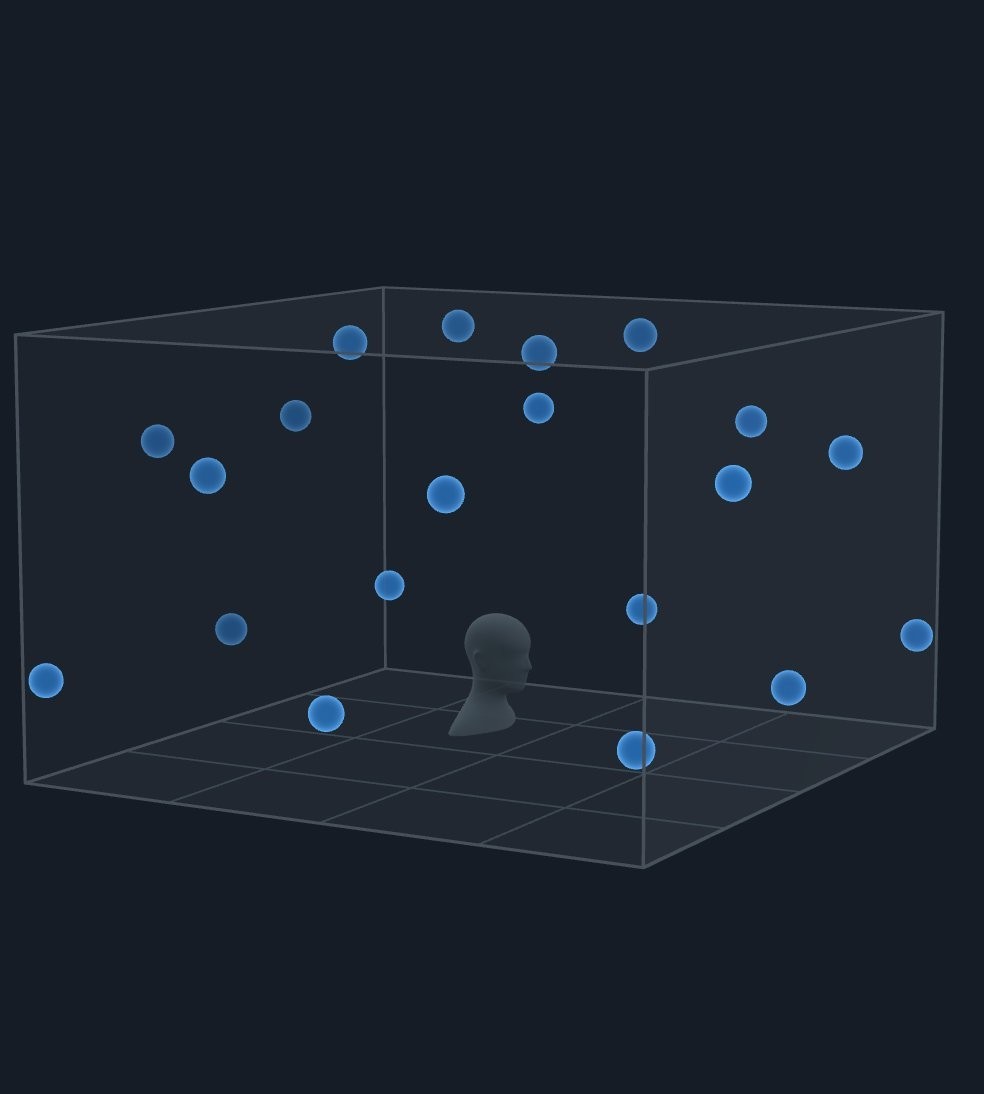

In most pop and film studios working with Atmos like Abbey Road or AIR, they record the music as usual, and then mix in a specialised studio with a 3D speaker setup like 7.1.4, and produced using Atmos’ renderer (shown below), which helps visualise the 3D scene.

For our production, I decided to try a different approach to the norm, partly as a response to the recording situation, where the ensemble would play the piece together in a large resonant space ie not multi-track / overdub, but also because I suspected there were sonic and workflow advantages to start the mix process in another spatial sound framework: ambisonics.

Ambisonics

I’ve used ambisonics in my own compositions for a few years, and enjoy both how it sounds, how it works, and its conceptual beauty. The format came about in Oxford in the 1970s through the Oxford Tape Recording Society. Michael Gerzon, Peter Craven, and others who were trying to record in 3D. They had a genius idea: you can use certain microphones to represent the harmonics of a sphere. Stack several mics together in certain configurations, or combined into a single multicapsule mic, and you can reconstruct a spherical sound field.

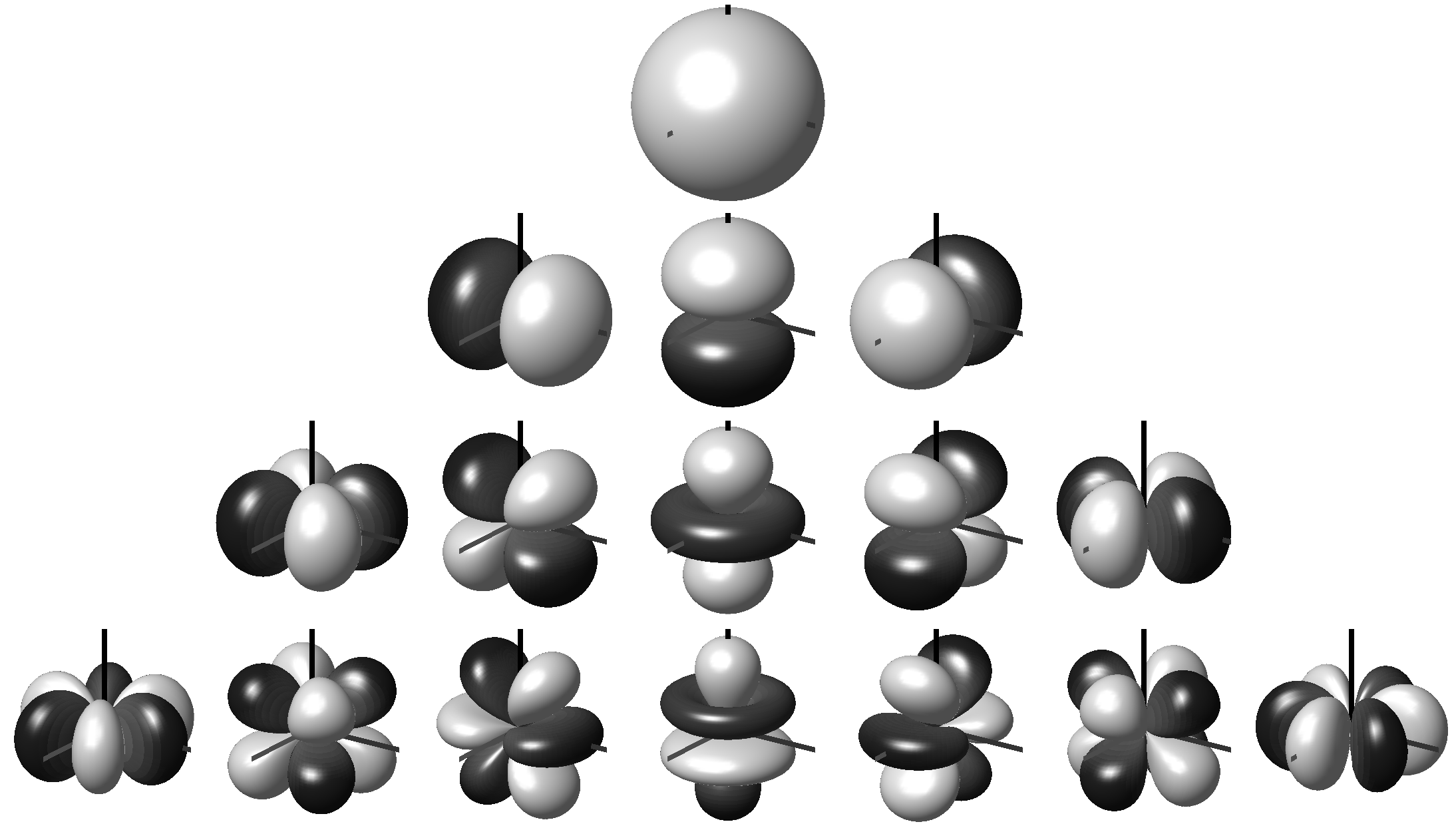

Spherical harmonics?! Yes, just like with sound, where a single timbre comprises of multiple overtones atop a fundamental, so too can a sphere be decomposed into multiple harmonics. Furthermore, the more mics you have, the more harmonics you can capture, and so the greater spatial resolution of your recording. We refer to this increasing degree of resolution as the ambisonic order. First order has 4 channels, second 9, third 16, and so on. See the image below for a representation.

Check out these examples of ambisonic mics:

Back to our production - I decided to record the piece using an ambisonic mic in the centre of the hall, plus spot mics on each instrument. I used the ambisonic mic like a mapping tool, almost like a holograph, so I knew where exactly to place the individual spot mics later in post-production. For the mix of murmurs, as it’s a quiet piece, and the instruments are fairly far apart, I ended up using mostly the spot mics, but with some sculpting to make them sound less harsh or less close, which might ruin the spatial illusion.

Just on this point, I might mention my thinking behind the overall album sound: I took a hybrid approach between classical and film style productions, where classical in its purist incarnation is all about capturing a space transparently, and with minimal changes to the sound in post-production (high fidelity recreation of a real life listener perspective), whereas in film, there is a greater emphasis on close mic techniques, and a sort of larger than life sound, not necessarily faithful to any single performance space, but rather, more fantastical virtual spaces.

I could have taken a purist approach with murmurs and used a single central ambisonic mic, but the piece is so quiet, the noise floor would be very high, and you would lose the special intimate and vivid quality I wanted with each musician. At least, in other recordings of similar spatial works that take a classical approach, I’ve found they sound a bit too ambient or murky. My mix is then, in a sense, hyper real, since you hear the players much more intensely or closely than would be possible in a real life performance.

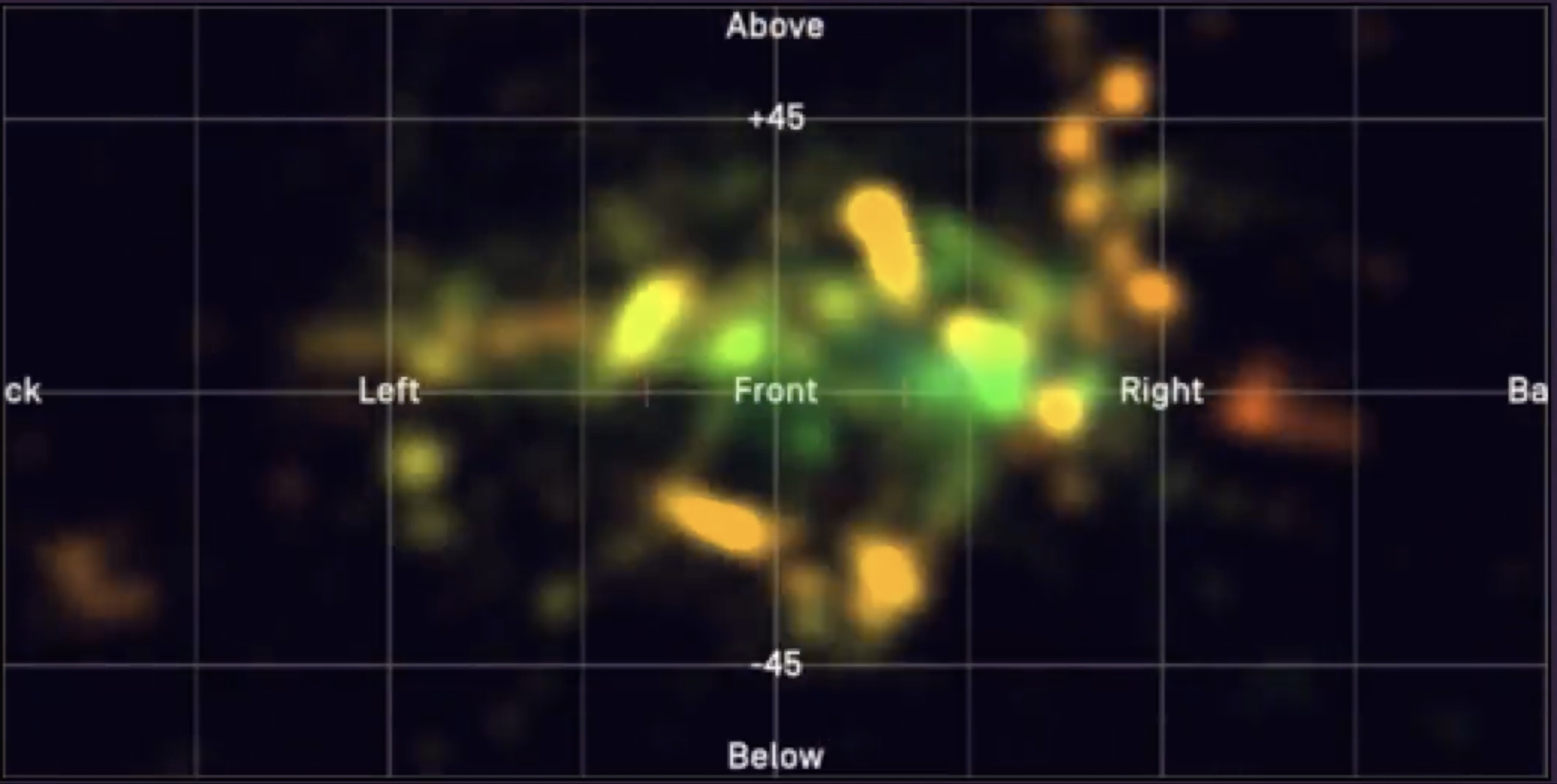

Blue Ripple

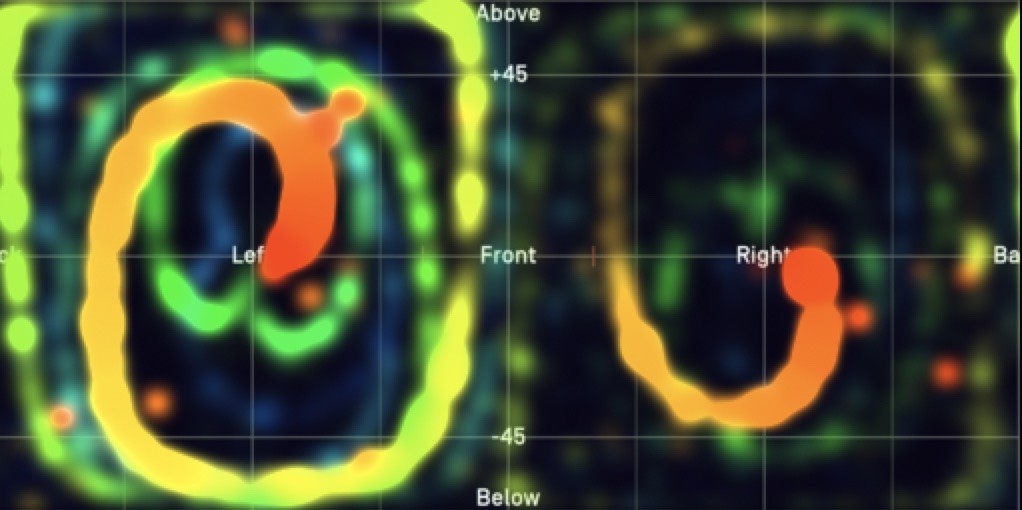

I’m lucky to have worked with Richard Furse and his company Blue Ripple for this project. Blue Ripple produce a suite of leading ambisonic tools, and I used these to create the master spatial mix of murmurs and the other three works. The image below shows a visualisation of the ambisonic sound field, where, like a world map, the sphere is rolled out as a flat 2D surface: the middle is front, and the side edges are the rear.

I could have done this in Atmos by using other spatial mics or mic arrays which neatly map onto Atmos’ preferred 7.1.4 format, but I really like the conceptual elegance of ambisonics, even if it introduced an extra step into my workflow on this record. Moreover, Blue Ripple has some extremely powerful tools such as convolution reverbs and various decoder packages, meaning I could ensure a certain degree of consistency across the album even though we recorded murmurs in a different space to the other works on the album.

The link then between this master ambisonic mix and Atmos is a new plugin from Blue Ripple, a decoder which converts the spherical ambisonic sound field into a virtual speaker dome, which can be imported into the Dolby Atmos Renderer, and then exported as an Atmos Master track. So, when you listen to our Atmos mix, you are hearing a dome of 20 virtual speakers which reconstruct the ambisonic soundfield.

Having produced the Atmos mix of murmurs, we decided to release the entire album in both stereo and Atmos formats, so I created Atmos mixes of the Dunn, Illean, and Miller works, again first in ambisonics, and then converted to Atmos via the virtual speaker dome. As I didn’t have an ambisonic recording of these three pieces to act as a spatial reference map, the panning aims to reconstruct a conventional concert layout, with the ensemble in front of the listener in an arc, albeit slightly more expanded compared to stereo. The field recordings in the Dunn are also more immersive, upmixed in ambisonics from stereo to 3D, plus the ambisonic reverbs on all three tracks add to the heightened sense of immersion.

This image shows Blue Ripple’s brilliant stereo to ambisonic upmix tool, which spreads the stereo source as two spirals.

Binaural

For people who don’t have access to Apple Music or Tidal, the two Dolby Atmos streaming services, we wanted to offer an experience of the spatial mix in a less tech dependent way. Included with the album along with the stereo and Atmos mixes is a special binaural mix of murmurs. This is rendered directly from the ambisonic master. With good headphones (ideally over ear, not in ear) you should feel as though the sound comes from outside your head.

Future

This project saw some huge learning curves for me, and I also encountered quite a few frustrating sonic and panning issues in Atmos, which I felt vindicated my initial choice of ambisonics as the format of a master spatial mix. Perhaps these bumps aren’t so surprising when, after all, the technology is bleeding edge things are changing at a rapid pace on both the production and consumer end. It will be interesting over the next few years to see how listeners adopt and become familiar with Atmos as a format.

There is a lot of hype around right now about Atmos and Apple’s Spatial Audio. We shouldn’t forget that this stems from commercial interests. I don’t think everyone needs to, or even should use Atmos. Stereo is incredible, and will probably forever be the default format for your everyday listener. Nonetheless, as technology opens up new experiences for creators and listener alike, I can foresee many exciting possibilities for new music tailored specifically for immersive listening formats.

I think we should really be thinking of it like a kind of musical VR, but better than VR, because the barrier to access is lower compared to VR tech. Plus, music platforms will hopefully remain more accessible and straightforward compared to the doomed metaverses of VR, despite the issues with pitiful royalties from streaming platforms. I can imagine some amazing work being made that use field recordings of real places, as well as completely artificial or imaginary spaces and musical processes.

In any case, we’re really excited with the results of our album, and we’d very much welcome your feedback. Feel free to get in touch via my website with questions about spatial recordings, Atmos, and ambisonics too!

Explore Ensemble: Perfect Offering is out now on Huddersfield Contemporary Records, distributed via NMC

NMC's Discover platform is created in partnership with ISM Trust.